Okay, let’s do this.

I can’t give Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri a star rating. It exists in a realm of moral ambiguity tantamount to Schrödinger-esque quantum mechanics, as it champions disobedience on part of a citizen against a corrupt and violent police force, whilst doing no more than at best paying lip-service to the people of colour who come most in contact with police violence and at worst trying to salvage the worst offenders for a white perspective.

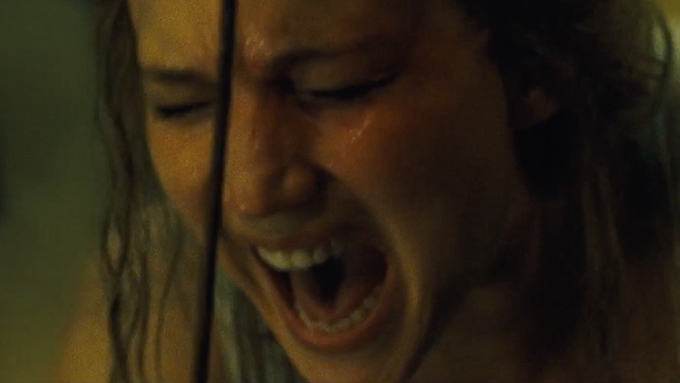

Three Billboards is, absolutely, exceptionally powerful in places. Repeated use of the phrase “Raped While Dying” sends emotional shockwaves, as it should. But, in a way, it’s also the problem. Mainstream Hollywood “issue films” are exceptionally wont to render questions of social justice and civil rights as wholly affect, no effect. In other words, there is no legitimate material analysis of the situation, which means that, when Mildred Hayes (Frances McDormand) storms over to Officer Dixon (Sam Rockwell) and inquires after the “[n-word]-torturing business,” it is very difficult indeed to believe she would have nearly as much a problem with the cops torturing “[n-words]” if they’d also managed to find her daughter’s killer.

This is largely because the suffering of people of colour at the hands of the police is never more than a (white) talking point, and a passing one at that: we’re told Dixon tortured a Black man pretty horrifically at some point before the film, but we never see him, we never hear his name. It’s nothing but a narrative device to help illustrate a white character. Mildred’s boss, Denise (Amanda Warren) is barely afforded a few “you go, girl”-s to Mildred before she is incarcerated for – you guessed it – possession in order to – guessed it again – get at Mildred. We’ve already had it established that the department holding Denise is in the business of torturing Black people so, will the camera cut to her, to see if she’s okay? No, we don’t know how she’s doing; we’re actually supposed to forget about her, but you bet your bottom dollar Mildred expresses her outrage all around the station. Might have been nice to visit her in jail even once, but we’ve got a one-woman war to wage, I guess.

Interestingly for a film whose plot is catalysed by the rape and murder of a teenage girl, Three Billboards actually takes an exceptionally dim view of all young women. Not one is portrayed as anything other than a ditzy, well-meaning but undeniably stupid girlfriend. Even the flashbacks of Mildred’s daughter, Angela (Kathryn Newton), show her to be irrationally volatile in such a way that her death is portrayed by implication as a – no matter how unjust – punishment for storming out the house.

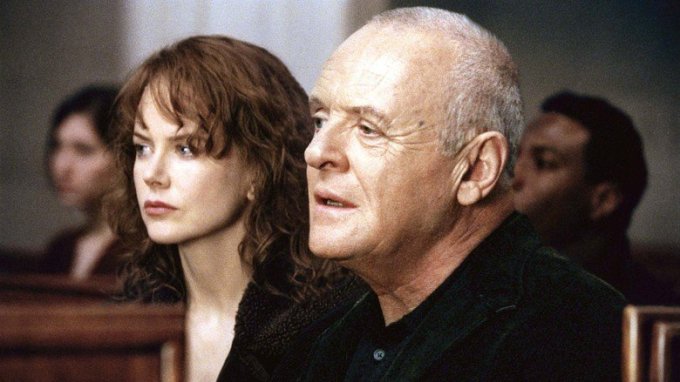

Chief Willoughby (Woody Harrelson) takes on an effectively messianic role throughout the film: a Good Cop™ who knows all our hearts’ desires, but not who killed Angela, it is he who promulgates Dixon’s supposed rehabilitation, informing him he has “love in [his] heart,” an insight that has escaped everyone else, audience included. Dixon takes it upon himself then to improve his actions, after having been fired for beating and throwing someone out a first floor window into traffic. Not arrested. Fired. He betters his ways through interactions solely with – yep – white people. Dixon’s increased importance as the film goes on shows him to be the avatar for any Trump voter in the seats, and the message Martin McDonagh wishes to convey is clearly one of largely liberal platitudes. “Hurt people hurt people” shouldn’t be such a stunning revelation to all the critics falling over themselves to give Three Billboards 5 stars for its “nuance,” and yet it seems to be its rallying cry. Unlearning oppressive thought and behaviour is acknowledged as uncomfortable, through its insistence on showing graphically the pain Dixon experiences in the second half of the film (in contrast to almost any of the pain experienced by his victims), but it gets so wrapped up in showing the discomfort, it forgets to show any unlearning.

The film had me laughing and tearing up in the grand majority of the right places, it’s nothing at all if not compelling, and the performances are fantastic. I’m especially glad to see the brilliant Caleb Landry Jones slowly climb the ladder, from first seeing him in The Last Exorcism, then Get Out and now to Three Billboards. Frances McDormand’s Best Actress Oscar will be well deserved. The film is, in occasional parts, beautiful, both visually and emotionally. However, there is an inconsistency and two-facednedness which is both ethically and morally suspect that it falls again into what may count either as tone-deafness, or indeed flat-out cynicism, which makes me want to avoid praising it too much at all. Its disquieting ambiguity is what I’m sure may have put Peter Dinklage in the first role I’ve seen him take in years that struck me as – for my perhaps patronising, able-bodied money – demeaning. The moment climaxes are reached, guns are drawn or buildings burned, Three Billboards has shifted out of clumsily handled dramatic thinkpiece territory and into “Martin McDonagh, director of Seven Psychopaths,” Tarantino-lite genre film territory, and the transition is not nearly as smooth as everyone involved clearly thinks it is.

McDormand is a powerhouse, and I’m not saying this would have solved every problem, but imagine if Mildred Hayes had been played by Angela Bassett. Same age, same wonderful talent and ability to combine comedy, aggression and heart, but one can only imagine how much the film would have been improved if the violence and indifference of the police expressed to Black people in the South had been the crux of the story, not anecdotal reference material. If murder that inspires all actions in the film had not been of the Young White Woman, the victim supposed to inspire sympathy, but had been someone as likely to be murdered by the cops as by any criminal. This is why #OscarsSoWhite should have been treated as a blessing for Hollywood – the overrepresentation of whiteness in films isn’t just a travesty of social justice; it stops cinema from being all it could be, too.