Like an awful lot of its ilk, Lights Out is a horror film made by people who believe that being quiet for a long time, then being loud briefly is the same as being scary. Thus, I’m exceptionally happy for the filmmakers that Lights Out is at least very scary by their own valuation, even if by virtually nobody else’s on God’s green Earth.

I walked in, knowing nothing about this film but figured within seconds of it beginning that this was basically an 80-minute version of one of those completely samey “3-minute horrors” on YouTube. I realised, as the end credits rolled, that, no, that’s exactly what this film was. Thus, the entire point of this feature-length adaptation appears to be the search for a narrative justification for the micro-narrative of the original short. Needless to say, I found the search distinctly frustrated.

Here’s the thing: some horror films work brilliantly with no explanations whatsoever. It’s good that nobody can say 100% for sure why, for instance, Jack is in the photo at the end of The Shining. Alternatively, there are many horrors that successfully balance heavy extrapolation – take, for instance, Martin or The Wicker Man – with a still greatly cinematic aesthetic. What doesn’t work at all is when you explain loads about half of something, then just drop it, and that’s exactly what happens here. All this does is confirm that you as a filmmaker had a premise, but no real insight whatsoever into the plot of your own film. It means your film is severely lacking in justifications and motivations but not because you’re representing a world of chaos; rather that you just aren’t a good writer.

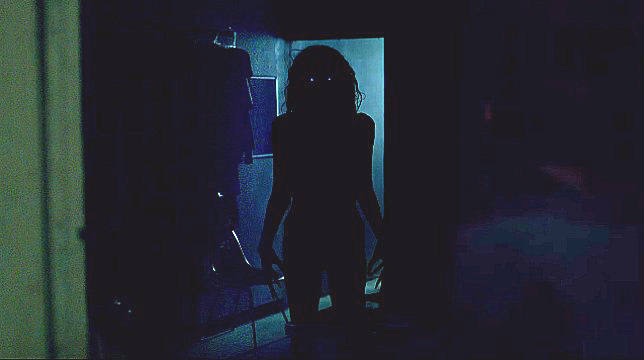

What we gather in this film is that “Diana” the supernatural antagonist, who exists only in the dark, definitely did exist as a human girl once but is now, like, a ghost? But she’s grown older? And she’s intrinsically connected to the mother’s mental state? But she still functions when the mother’s been knocked unconscious? Seriously, in terms of logic, this film is driving on empty.

I remember when I walked back home in a quietened daze from the first time I saw The Babadook, I said without a hint of irony or reservation that the family-based abuse-metaphor psychological horror filmmakers may as well just pack up shop: whatever hadn’t been covered to perfection the first time round by The Shining had absolutely just been covered to perfection by The Babadook. Because I understand The Witch in somewhat broader gender-oriented and theological terms, nothing has successfully shaken my opinion since – Lights Out is not merely no exception; it is in fact re-confirmation.

In The Shining, the monster is not merely the abusive father, rather the great old evil behind all such events – it is a force patriarchal, racist, misogynistic, addiction-enabling and murder-encouraging. This is why there’s little to no contradiction when all the symbolism points to the ghosts being part of Jack’s own mind (for instance, the fact that, every time he speaks to one, he’s stood before a mirror/reflective surface) and yet they reveal themselves to have power and presence separate from him (Grady’s ability to open the pantry door, Wendy’s visions etc). In The Babadook, the monster 100% reflects Amelia’s grief, pain and despair in the face of what she perceives as the intrinsic connection between her husband’s brutal if accidental death and the birth – in fact very existence of her “problem child,” Samuel. Its existence as an entity separate from her is as nuanced as the distinct between anyone’s personality and their mental illness. Thus, the answer to the question “is the monster real, or is it just a representation of a mother’s anguish?” is, of course, a resounding and simultaneous “yes” to both. No such nuance in Lights Out. The remarkable imbalance in this film leaves the meaning behind Diana’s presence entirely nonexistent, and yet mother Sophie still appears, in everyone’s esteem, entirely to blame.

The Shining and The Witch might both most simply be described as horror films about a family desperately tearing itself apart, whilst The Babadook may most simply be described as a horror film about a family trying desperately to piece itself back together; Lights Out seems to have the type of philosophy of family Robin Wood described in “The Lucas/Spielberg Syndrome,” charming, yet entirely motivated by a brutal neoliberal ethic. If a member of the family is too mentally unwell to fulfil their role satisfactorily, it’s best they just kill themself, so the rest of the family can carry on without them. Thus, what is most insidious (no pun intended) about Lights Out is not the horror at all, but the attitude it takes towards mental illness – one as mercenary as it is antediluvian. Even within the grand scheme of cookie-cutter jump-scare horrors, this film stands out as one worthy of particular reproach.

(Additional note: so what? The stepfather was a neuroscientist who worked at a mannequin factory? Why do they never explain what all the mannequins are doing everywhere?)

⭐